Here's a news item that was widely syndicated in late December 1925. This occurred during Houdini's

3 Shows in One at the National Theater on 41st Street in New York City. An evening with Houdini was never dull!

|

| The Cincinnati Post, Dec. 30, 1925. |

Nino Pecoraro (misspelled Pecoriaro in the above) was an Italian spiritualist who claimed his spirit guide was the deceased medium Eusapia Palladino. Pecoraro's reputation was greatly bolstered when he impressed Sir Arthur Conan Doyle during a seance at the offices of the American Psychical Institute in New York City in 1922. However, Doyle was dismayed when full details of the seance appeared in newspapers the next day "with the copyright mark below it, to show that it had been duly paid for."

The incident at the National wasn't Houdini's first encounter with Pecoraro. In 1923 the famed "boy medium" was tested by the

Scientific American committee on which Houdini served. Houdini was on tour and did not attend the first two tests, during which Pecoraro impressed the committee with his ability to manifest ghostly phenomena while securely bound. The head of committee, J. Malcolm Bird, who would later collude with Margery, even wondered if the smell of garlic on the Italian's breath could be "celestial garlic." No joke.

Things looked good for Pecoraro. That is until Houdini arrived for the third test on December 18. He was mortified to see the committeemen securing Pecoraro with a single piece of long rope. Houdini cut the rope into pieces and tied the medium himself. That put an end to Pecoraro's ghost show and his shot at the

Scientific American prize. (For an excellent account of all this check out

The Witch of Lime Street by David Jaher.)

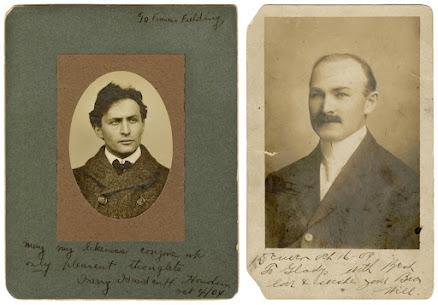

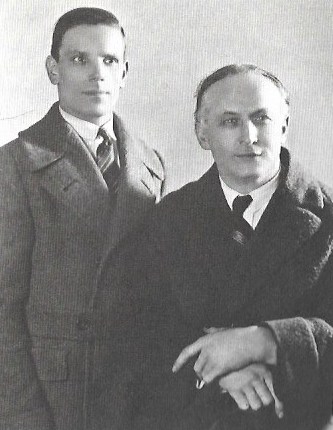

While Houdini biographies all contain the story of the Scientific American tests, none of them mention this follow-up incident at the National. Was it really a "riot"? One thing I find intriguing is the photo below. This shows Houdini and Pecoraro around the time of this confrontation. In fact, Houdini and the young medium took a series of portraits together at a New York photo studio. Why would they do this? Were they planning a public test, as alluded to in the article, that never came to pass? Could the theater incident have been a publicity stunt that got out of hand? There may be an untold story here.

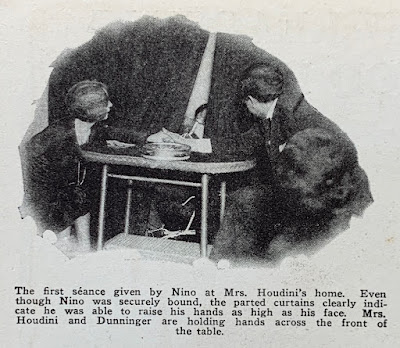

After Houdini's death, Pecoraro gave Bess a private seance at her home on Payson Ave. Joseph Dunninger was also in attendance. Nino went through his regular routine but failed to deliver the all important Houdini Code to Bessie.

In 1928 Pecoraro was at it again. This time the medium offered to produce Houdini's physical spirit at the offices of Science & Invention magazine which offered a $21,000 prize for genuine spirit phenomena. Bess attended the seance and cameramen surrounded Pecoraro's cabinet, ready to snap a photo of the master magician. Nothing happened. "Not Even for $21,000 Would Houdini Show Himself at Seance" read a newspaper headline the next day.

A few days later Joseph Dunninger recreated Pecoraro's seance using trickery for better results. The photo below shows "Houdini" making his reappearance with Bess looking on. Pecoraro's manager, Charles E. Davenport, asserted that Dunninger had mediumistic powers even if he didn't know it.

In 1931 Pecoraro finally confessed to being a fraud. He demonstrated his methods, which included producing a message from Houdini, at a New York press conference. The resulting United Press story is pretty amusing.

|

| The Ogden Standard Examiner, April 9, 1931. |

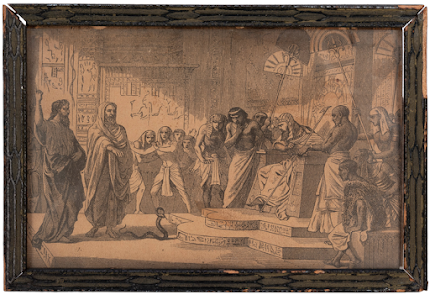

It's unclear if Pecoraro ever did become a cement salesman, but he did continue to paint. In fact, two of his paintings are on exhibit at the Houdini Museum in Scranton, PA.

On April 27, 1973, Pecoraro collapsed while walking with a friend in Naples and died on his way to the hospital. He was 74.

|

| Painting by Nino Pecoraro at the Houdini Museum in Scranton. |

Thanks to the Houdini Museum in Scranton for the photo of their Nino painting. Other images come from Houdini: A Pictorial Life

by Milbourne Christopher, Houdini's Sprit Exposes

by Joseph Dunninger, and Newspapers.com.